|

THE LEATHER-BOUND

BOOK

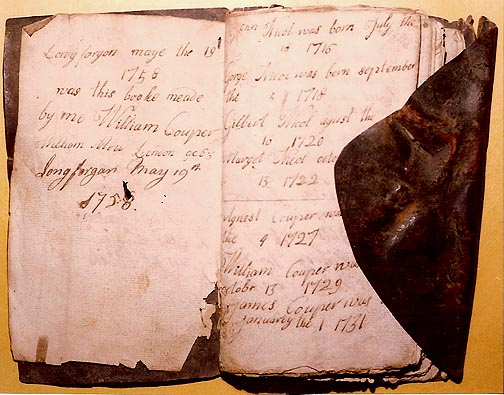

William Couper II Accounts, 1758-1782

William Couper III (1775-1855) brought with him to America a small

Leather Bound Book that was written by his father in Longforgan,

Scotland.

This was later analyzed by Monroe Couper, in 1976, and the transcript is

located below

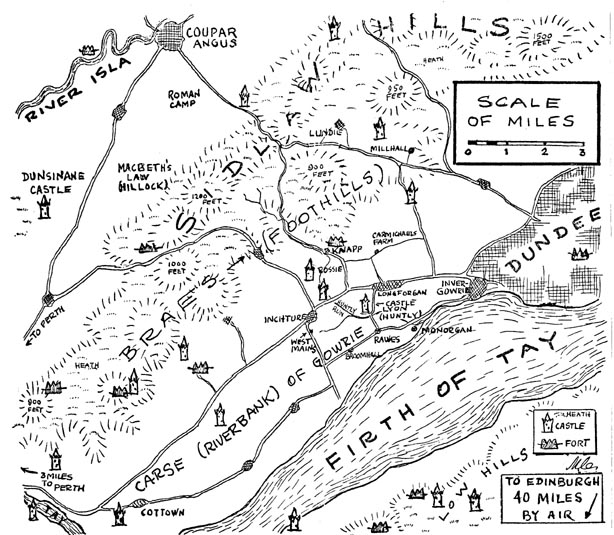

The book was an account of renting land around Castle Huntley (then

Castle Lyon), growing flax, weaving it into linen, and the 8 children that

were born in Scotland. It was begun in 1758 by William Couper II

(1729-1811) father of the immigrant. An earlier son also named William

died very young, so William III, the immigrant, was given the same name. |

|

|

In

May 1758, William Couper II, of the Rawes (Row Houses) of Castle

Lyon, in the parish of Forgan and Shire of Perth, Scotland, made himself

an account book from seven sheets of legal paper (watermarked with the

Royal Arms), a covering of leather and some string. The sheets measured

six by eight inches. Stacked and folded at the middle, they gave 14

leaves or 28 unnumbered pages. He wrapped the leather around them with

a flap to hold the book closed. The final size was 6 ½ inches high and

4 ¼ inches across. Inside, William noted who had made the book, the

date and the name of his village, Longforgan.

The occasion, we can

surmise, was that he was going into an enterprise on his own. His

father, now in his sixties, was a weaver of flax. Linen had been an

important Scottish product for centuries. Thirty years earlier, a colony

of Protestant French people had been brought to Edinburgh to teach the

spinning and weaving of cambric. Even before that, his father had

married the widow of a weaver who had died in his prime. It was the

continuation of that weaver's business, already established in 1718, and

extended by William's father and mother, that he was recording in his

new book that Spring, when he listed for the year 1758 the workers

supplying the flax (lint) which was the raw material.

Perhaps, at 28,

William younger had acquired the experience and judgment his parents

thought necessary for him to assume the responsibility. More probably,

his mother was failing seriously or had died. Her death would have ended

the lease on the farmland where they grew their own flax as well as

food. This lease or tack, which we still have, had assigned the lands

and houses to John Nucoll (or Nicol) and his spouse "all the days of the

Lifetym of the longest liver of them two." Isobel, the Spouse, had

survived John Nucoll to marry William Couper and to become the mother of

William younger. He would now be the logical new tacksman in the

family.

In any event, in

the second Spring after he had started his book, i.e., in 1760, William

younger contracted to occupy land and buildings from the Countess of

Strathmore, proprietress of Castle Lyon. He would gain entry to the

yards at Easter; the house and grass at Whitsun, 7 weeks later; and the

arable lands at harvest. Then at Martinmas, November 11, with all in

readiness, William married Isobel Deuchars. As the new family started

and grew, William's book recorded the events. He skipped over to page 12

to enter births. The intervening pages filled up with business records.

Page 12 became filled with birth of the fourth child, and flax listings

had already passed this page, But William had had the foresight to

reserve page 11 for the last four children.

After 1771 he

probably started some other form of bookkeeping, partly because the book

was filling up. In 1763 he had begun a list of crop rotations on p. 26

and had to continue it on p. 25. About the same time he chose p. 20 to

list tailoring expenses, and 15 years later he put more on the final p.

28. And so, over the final ten years until 1782, he filled the remaining

blanks in the book wherever he found them and whenever he thought it

prudent to have a record: rent, funeral expense, blacksmith contracts, a

prayer, lime hauling, even a grocery list. Occasionally the children got

hold of the book, sneaking in some entries of their own.

The little volume

is in surprisingly good condition now in 1976, after more than 200

years. Though the pages are yellowing and the ink pale in some places,

most of the writing is still strong and bold, the string tenacious

though partially replaced a century ago, the cover still tough and

snappy and the spelling constantly fresh with vigorous surprises. In studying,

researching and more or less living with this book for the past few

years, I have come to feel myself a kind of foster member of the family

at that time: With a little empathy you can share some of the

ruggedness, where

Wm. Sr. in

his seventies was still turning out his four bushels of yarn a year,

added to by the many relatives and neighbors from Longforgan and other

villages. The farming could only have been grueling and one has only to read the

exacting detail of the leases to grasp how much labor as well as crop

had to be promised to the Castle personages at this time when the

residues of serfdom, though waning, had not quite been eliminated from

Scottish agriculture. Only four of the Coupers' eight children lived to

maturity [this accounts for more than one William]. From the letters of

one of them, the William who came to America (in 1801, bd 1775-1855), we

learn his opinion that, had he stayed home, he could never have become

independent, no matter how hard he had worked. But on the brighter

side, there were high energy and specific evidences of persistent

industry, system and planning, as well as family affection and loyalty.

William younger, author of the book, wanted his son William back from

America. The latter never quite got over his longing for home, although

he knew he could never go back. He rejoiced with every family contact.

When his father died, he gave his share of the inheritance to his

struggling brother John, in Scotland, which he said needed it more than

he did. And there was accomplishment. One son of William younger not

only continued the weaving trade but became a doctor as well. Among the

grandchildren in Scotland were manufacturers and professional people.

The little leather

book gives us a glimpse of our family (this one small branch of it)

making the transition from the last bit of serfdom into private

enterprise, probably before serious impact from the industrial

revolution.

Monroe Couper, Hockessin, Delaware, January 1976

|

A Broad View of

William Couper's Business

Excerpts from

History of the Modern World by R: R. Pa1mer and Joel Colton

In the fifteenth

century Englishmen began to develop the processing of wool in England.

To avoid the restrictive practices of the towns and gilds, they "put

out" the work to people in the country, providing them with looms and

other equipment, of which they generally retained ownership. This

domestic system of rural household industry remained typical until the

introduction of factories in the late 18th century.

It was clearly

capitalistic. On the one hand were the workers, employed as needed,

receiving wages for what they did. Living both by agriculture and

cottage industry, they formed an expansible labor force, available when

needed, living, by farming when times were bad On the other hand, the

manager purchased the needed materials, passed out fiber to be spun,

yarn to be woven or dyed, paying wages for services rendered and keeping

the coordination of the enterprise in his head.

An English estimate

in 1739

held that 44¼ million persons "engaged

in manufactures" in the British Isles, This would comprise almost half

the entire population, including women and children, working-

characteristically in their own cottages under the domestic system.

Half were in the marking of woolens, others in copper, iron, lead, tin

wares, leather and smaller trades were paper, glass, porcelain, silk and

linen. Smallest of all was cotton, with 100,000 workers.

Great Britain had no

internal tariffs, insignificant gilds, no monopolies (except to

inventors) and was the largest internal free trade area in Europe.

Economic activity was largely domestic, between town and town, or region

and region. So William's business can be assumed to be of the above type

since this accounts for the records on the several types of flax/linen

products, and the varied and fluctuating list of workers. But

William remained a small operator, contributing his own and his family's

labor and running his farm.

Return To HOME

Page

|